O Wonder!

How many goodly creatures are there here!

How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world!

That has such people in’t”

-Miranda, 5.1.181-4

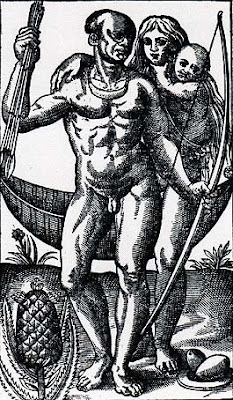

The first recorded performance of The Tempest took place on Hallowmas Night 1611, “before the kinges Majestie” at the Palace of Whitehall. The production came 119 years after Columbus’s landing on the island of Guanahani, four years after the foundation of England’s first permanent colony across the sea and on the heels of the well-publicized 1609 wreck of the ship Sea Venture off the coast of Bermuda. Several accounts of this shipwreck appeared in London in 1610. Public curiosity for such chronicles and reports ran deep. A 1588 account of a trip to the colony at Roanoke by the great English polymath Thomas Hariot, containing meticulous proto-ethnographic detail about the native Algonquian Indians and illustrated by powerfully evocative woodblock prints, was translated into four languages and became a best-seller across Europe. This profusion of public fascination must have been a particular draw for audiences to The Tempest. Shakespeare capitalized on this allure - what Joseph Roach calls the play’s “vicarious tourism” – and even satirizes it in the second act, when Trinculo says that while an Englishman, “will not give a doit to relieve a lame beggar, they will lay out ten to see a dead Indian” (2.2.32-34).

There is no question that, in order to unravel such a complex historical document as The Tempest, one must examine the context of society, time and place out of which it was conceived, but this enterprise of comprehension can also go the other way. Details about the culture and mindset of early Stuart England are preserved in the play, as an insect in amber. The Tempest provides us with an invaluable window into the early 17th century European imagination, and the ways in which the average English soldier, tailor or fishmonger might have construed the flux of information coming from the New World, at a time when the discovery and exploration of these hitherto unknown lands significantly expanded popular conceptions of the earth, humanity and knowledge. In The Tempest, Shakespeare begins to sift through the emotions aroused by these discoveries: reveling in the thrill of discovery, exploring and exploiting popular curiosities and, in the haunting and illusive character of Caliban, understandings of the native “other.” This reading of the play, in turn, reveals in the thorny contradictions of Caliban’s own discourse, not only a striking apprehension of the beautiful intelligence of the native, but also an intense resistance to invitations of community, which discounts the possibility of eventual accord.

While there is no consensus among Shakespeare scholars that Caliban is even meant to represent a Native American, textual and contextual evidence indicates that this interpretation is the most sensible explanation to his symbolic identity. The proximity of the play’s composition to Strachey’s account is reflected in Ariel’s line about Prospero calling him “at midnight to fetch dew/From the still-vexed Bermudas” (1.2.229). This line, along with Stephano’s worry that tricks are being played on him by “savages and men of Ind” (2.2.57), constitute direct allusions to contemporary explorations that would have been instantly recognizable to Shakespeare’s audience, and provide sufficient evidence for one to read The Tempest – at least in part – as a play about the encounter between the Old and New Worlds, and a consideration on future relations.

Shakespeare has designed Caliban as an intimation of a native American, with “his closeness to nature, his naiveté, his devil worship, his susceptibility to European liquor, and above all, his ‘treachery.’” Yet Shakespeare does not typecast the native, refusing to endow him with any of the obvious physical reference points (no feathers, no arrows, no tobacco, no body paint, etc.) Just as Shakespeare muddles our sense of place by overtly referencing New World exploration while explicitly setting the play’s island in the Mediterranean (between Tunis and Milan), he dissociates Caliban from the usual symbolic tropes of the native in order to present the character for the audience’s interpretation in a neutral environment. Shakespeare wants his viewer to know that Caliban represents a Native American, but is not actually one.

Perhaps the most surprising thing that Shakespeare does with Caliban is to challenge the prevailing understanding of Native Americans as being intellectually inferior to Europeans. Why else, Europeans thought, would Native Americans be without such basic technology as the wheel and metal tools? An extension of this mode of thinking was in the European belief - informed by the apparent Apotheosis of Cortés by the Aztecs and an inflated sense of their own cultural and moral supremacy – that Indians viewed them as gods. The Tempest promotes this self-deification of Europeans in the New World through Caliban’s naming of Stephano as “a brave god” (2.2.112), and its representations of Prospero’s assumption of control on the island.

Prospero’s magic becomes the force of law by which he subdues the native Caliban, just as European technology – particularly their guns – allowed them to subjugate the native peoples encountered in the New World. Prospero’s magic imbues him with the god-like abilities to conjure tempests out of thin air and summon goddesses from Greek antiquity for the masque in Act IV. Just as Native Americans first interpreted the flash of smoke and roar of thunder let off by the Europeans’ strange staffs as magic, Caliban is both wondered and cowed by these displays, contending, "I say by sorcery he got this isle;/From me he got it." (3.2.52-3). Shakespeare, however, undermines this understanding through the knowledge that Prospero’s powers come not through some innate propensity for magic, but from his books, a fact which substantially subverts the audience’s understanding of the power dynamic between Prospero and Caliban. Caliban, no fool, recognizes this as well, telling Trinculo and Stephano, “Remember/First to possess his books, for without them/He’s bot a sot, as I am,” (3.2.91-93). It is not through inbuilt primacy, but by lucky possession of material objects that Prospero has dominion over Caliban.

This symbolic reduction of European superiority would be interesting in its own right, but Shakespeare endows Caliban with the most lyrical and expressive lines in the whole of the play. In Act III, Caliban comforts Trinculo and Stephano by telling them, “Be not afeard. The island is full of noises,” and launches into a rhapsodic and emotional description of the dream-world of his home:

Sounds and sweet airs that give delight and hurt not.

Sometimes a thousand twanging instruments

Will hum about mine ears; and sometimes voices,

That if I had waked after long sleep,

Will make me sleep again. (3.2.135-140).

Caliban’s speeches are striking in their eloquent articulation of the island’s unique and inscrutable beauty. The other characters refer to its strangeness, but the audience would have little notion of the island’s characteristics or play’s sensory setting if not for Caliban. In this way, Caliban is at once the play’s most alien character, and its chorus. As Trinculo and Stephano are the play’s representations of the common man, Caliban serves as ambassador and tour-guide not only to them, but to the audience as well. Caliban’s manifestly keen mind has not only learned the tongue of his conqueror, but has mastered it. His verbal dexterity gives him an extraordinary ability to evoke the sights, sounds, and smells of the island, and puts to shame even the words of even the educated nobles. Caliban’s denunciation of Prosper, “You taught me language; and my profit on’t/Is, I know how to curse. The red plague rid you/For learning me your language” (1.2.366-368) is particularly compelling and consequential precisely because of his gift for language, only fully revealed to the audience, or Stephano and Trinculo. With this line, Caliban, and with him Shakespeare, reject assimilation as impossible.

Through the contrasting identities of Caliban as the “savage and deformed slave” and eloquent spokesman, Shakespeare presents the essential duality of the Native’s identity. Caliban is at once wholly human, and indelibly precluded from joining the other humans of the play by his otherness. The immense melancholy of Caliban is the diverting tragedy of The Tempest, by all other accounts a classic romance. Caliban is astute, sardonic and perspicacious; it is only the arrival of the Genoese that defines his deformity into relief and robs him of his humanity. Though he shows the capacity to learn the manners and language of these outsiders in his world, he can never be one of them. This same duality of definition seems to mark Shakespeare’s understanding of the native peoples of the New World. They are wholly human, though totally irreconcilable to the European conception of humanity. At The Tempest’s end, Caliban is left alone again, with his island and humanity his own once more. Alas the “goodly creatures” of Shakespeare’s real “brave new world” were not so lucky.